Photography By The Numbers

At a recent gallery talk I gave on my work, a student asked how many pictures (exposures) it took to “get a good one?” When answering the question as best I could, I realized that it was much better question than I first realized. I wondered if the student would ask the same question to a painter, or, how many paintings do you have to paint, before you “get a good one?”

When you do the math, the archives of some photographers can reveal the chance of “getting a good one,” is more difficult than numbers can imagine.

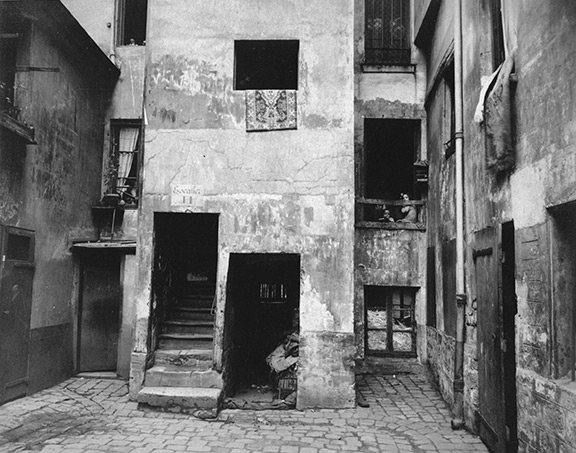

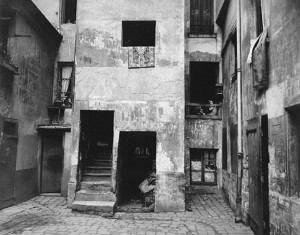

Eugéne Atget, Rue Boca 41, Paris, France

Eugéne Atget, the french photographer who started it all, made about 8,500 glass plates in his career along with thousands of prints. His lyrical documentary style made most of his work interesting enough that another photographer, Berenice Abbott, worked most of her photographic career caring for and telling the world about Atget’s work.

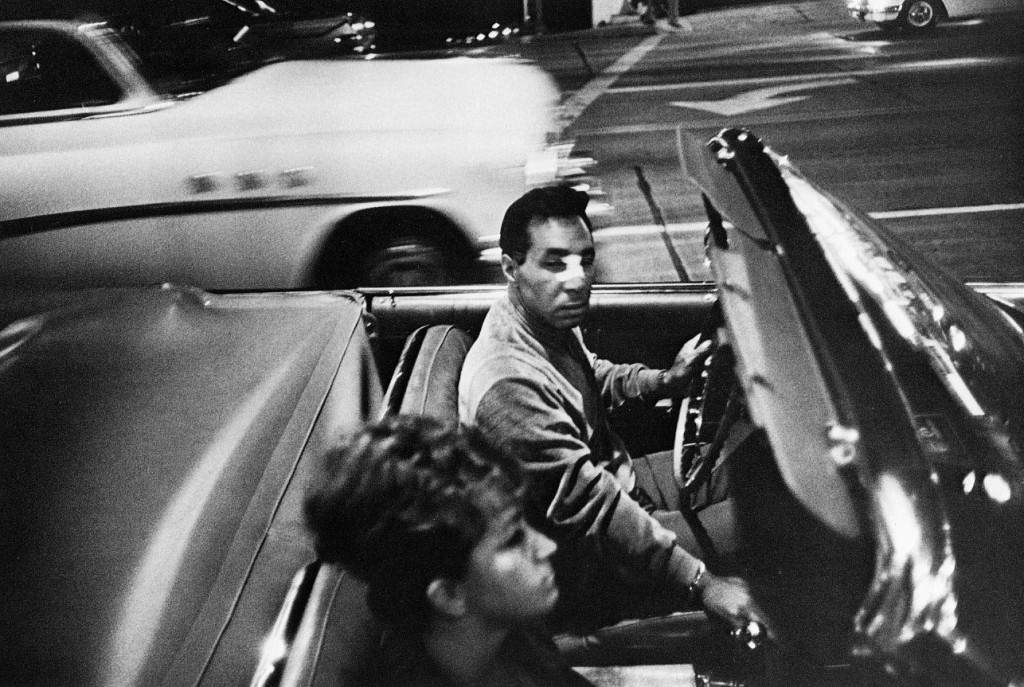

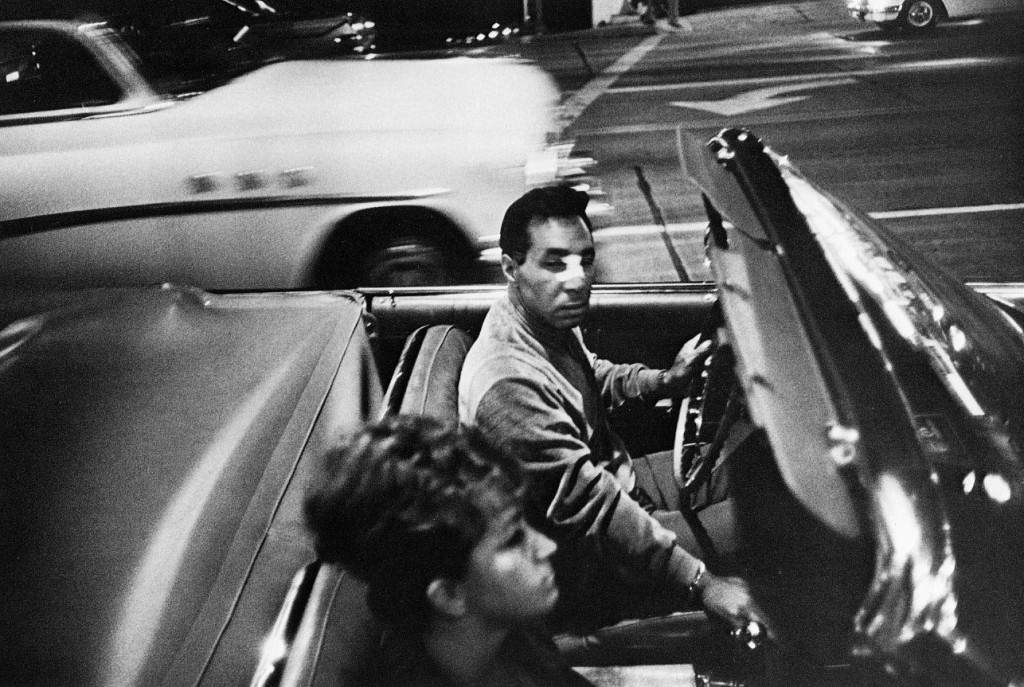

Robert Frank Editing His Negatives

Robert Frank exposed 759 rolls of film, or about 27,000 frames of Tri-X Pan to fill the book, “The Americans,” which eventually had 83 photographs in it. To do the math on how many exposures it took Robert Frank to get the “good ones,” for his book “The Americans,” it would be 27,000 ÷ 759 = 325, or, once every 325 snaps of the shutter. Not bad.

At a recent lecture I attended, by a very famous photographer, told the audience that he had exposed over a million frames in his photographic career. He noted, though, that he could only recall a couple pictures that he thought was worth the trouble; cross my heart, and hope to die.

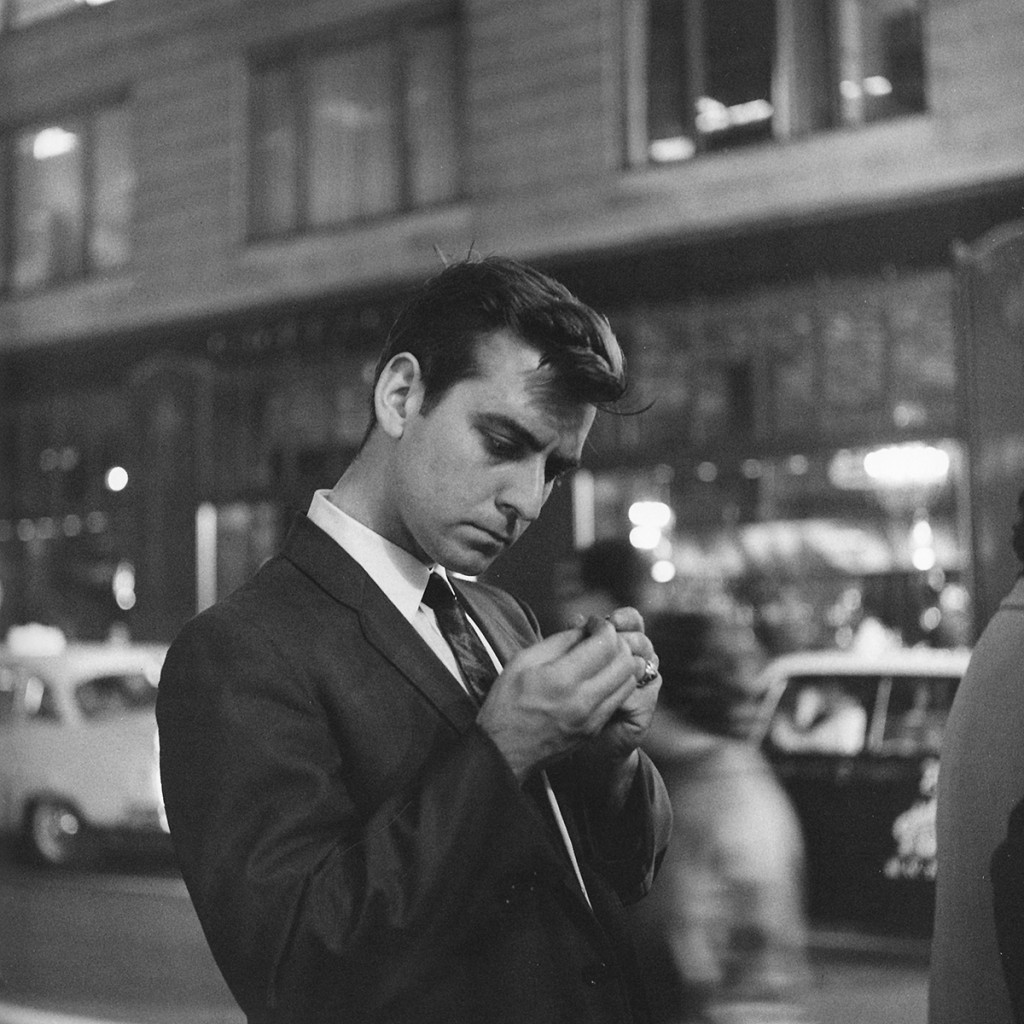

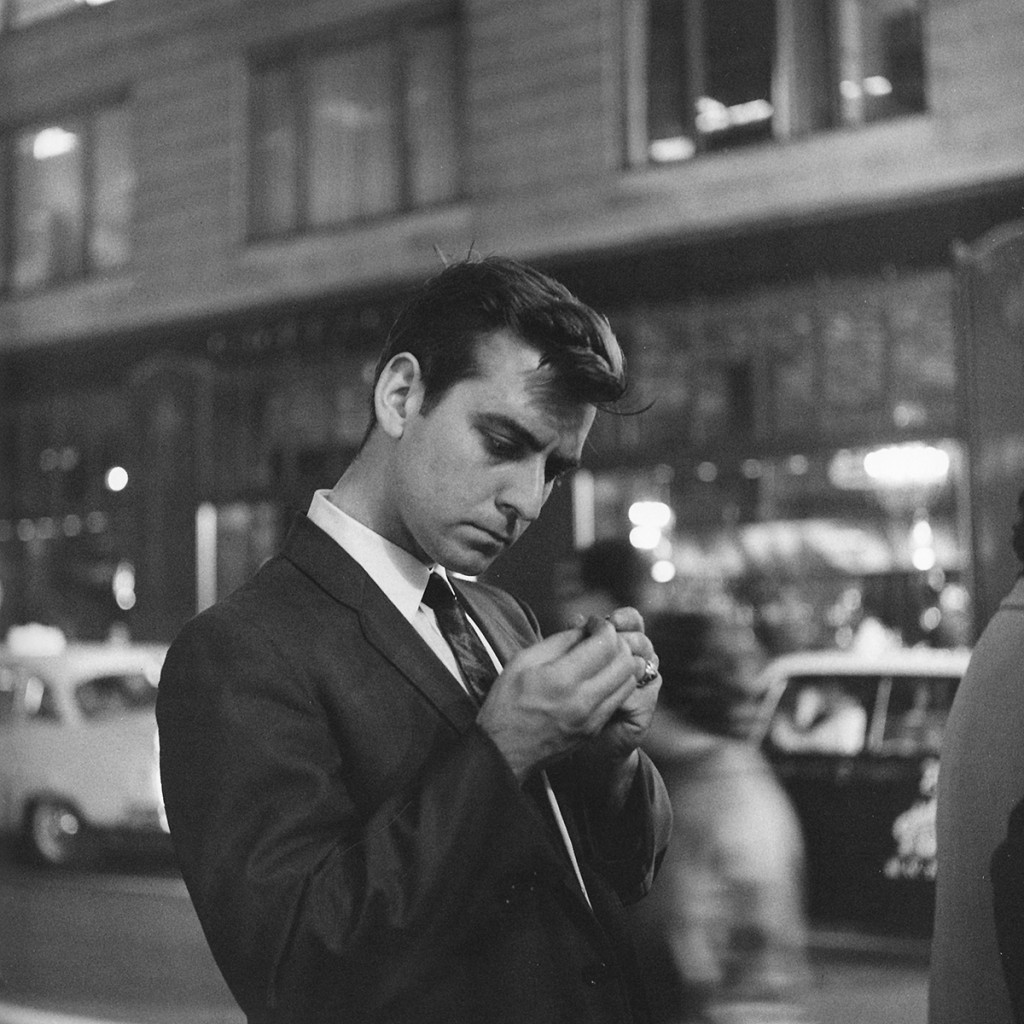

Gary Winogrand, Los Angeles, 1964

Gary Winogrand, according to photographic legend, at the end of his life, left over 2500 rolls of film or about 90,000 frames of exposed but undeveloped film in his freezer when he passed in 1984. After processing and proofing the film, Winogrand’s descendants found only a few images on the proof sheets worthy of Winogrand’s work as a photographer.

Vivian Maier, Downtown Chicago Loop, 1968

Vivian Maier, who has recently surfaced with medium format (120 size film) street work, is rich with tone and meaning about her life as a spinster nanny and her love affair with the camera. Her work was discovered during a storage locker auction and what was found were ten of thousands black and white and color transparencies and possibly a thousand of exposed but undeveloped rolls of film. Her two posthumously published books show two completely different perceptions of what she thought important for her camera. The later of the two being the better book, (these publishers also published posthumously a volume on photographer Richard Nickel, another Chicago native) reveals a humanistic understanding of her personality and also the more abstract images she made at the end of her life.

For the record: there is absolutely no mathematical ratio which determines how many pictures it takes to “get a good one.” What really matters is what you point your camera at, and after that it’s your ability to edit your work to reveal those few pearls laying around your proof sheets, which is ultimately your only reward.

All Content ©Copyright Craig Carlson 2012 All Rights Reserved