The Journal of San Diego History

University of San Diego

Jack London, Photographer, An exhibition at the Maritime Museum of San Diego

(Through December 3, 2012)

Reviewed by Craig Carlson, Lecturer, School of Art Design & Art History, San Diego State University

If Jack London had a calling card it probably would have been emblazoned with the photojournalistic code “f/8 and be there.” f/8 is the aperture in a lens with the greatest optical sharpness, and – like Henri Cartier-Bresson would do with his career – London had an acute awareness of being at the right place at the right conflicts of his time. The camera (as opposed to the sensationalist yellow journalism being simultaneously practiced during the turn of 20th century) is the great truth detector. Photographs never lie; people do.

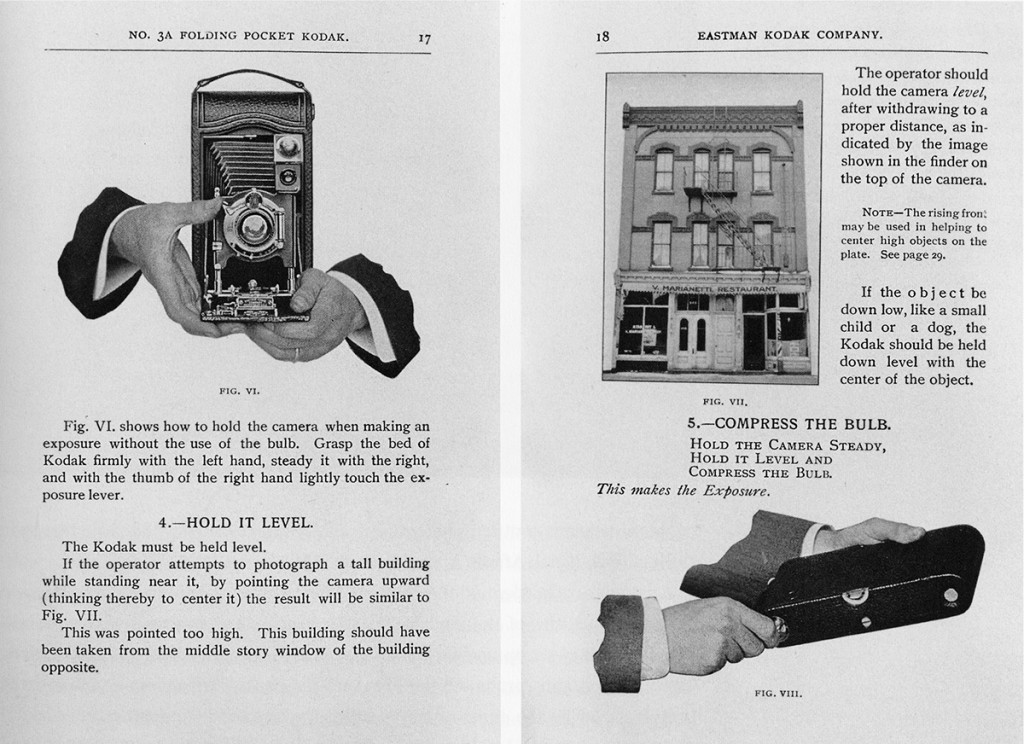

To situate London’s work as a photographer, one must understand that he was an early pioneer at the turn of the 20th century using the first hand-held cameras using flexible roll film (made for amateur use) as opposed to the heavy, large glass plate cameras (tripod required) often used by professional photographers of the era. Film emulsions and lenses were slow to collect light and a steady hand was needed to shoot dynamic, changing events in the streets (later called “spot news” by photographers).

London certainly had the “right stuff” to be a photojournalist. One requirement was not minding working around starving orphaned children or with open saddle sores, or for that matter, being arrested for taking a snapshot of a Japanese blacksmith during the Russo-Japanese War. One also needed an ability to tolerate the obligatory boredom. What matters with Jack London’s photography is not his style, but the very content of his photographs. I agree with Philip Adam on the notion that making photographs is a two-step process: first looking for and understanding your subject, and then seeing it with the camera eye.

Adam lent his hand in the darkroom and made the prints from London’s vintage negatives for the beautifully printed volume that bears the same name as this exhibit. I assume there were some difficult nights for Adam while printing London’s out-of-focus and often under- and overexposed negatives. However, by far the most difficult part must have been staring into the abyss of human suffering that scored most of London’s early photojournalism bound for content in American papers and his imagined self-published books.

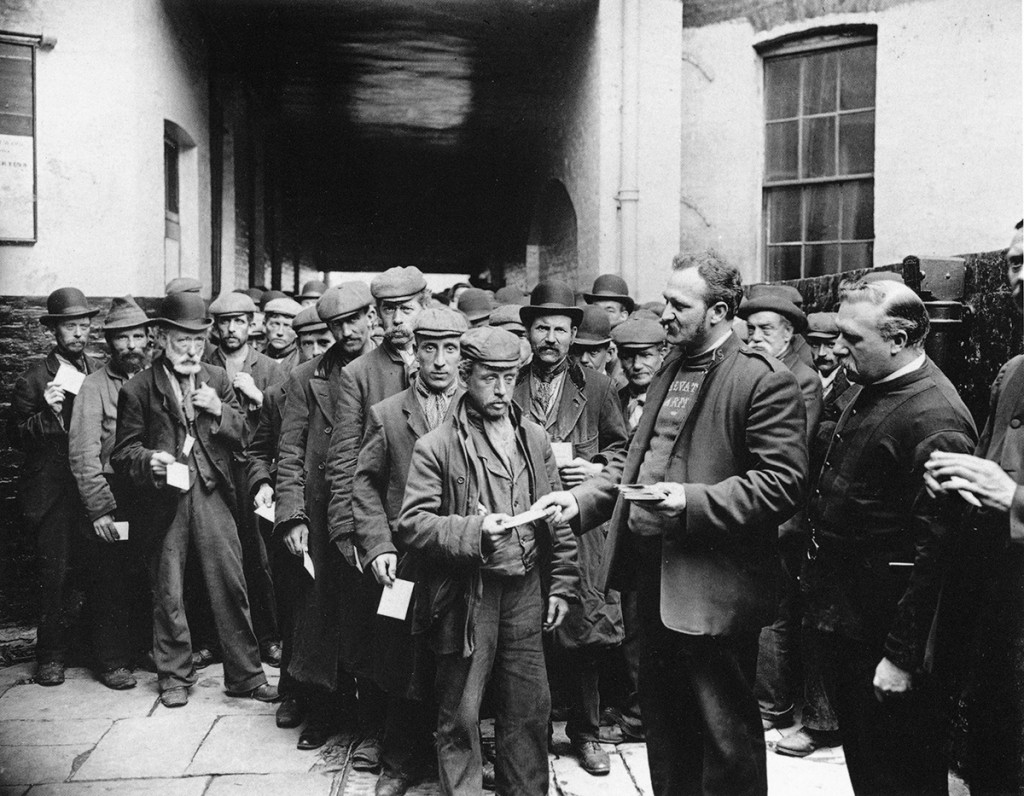

Court Yard Salvation Army Barracks Morning Rush–men who had had tickets given them during the night for free Breakfast, London, 1902

Arriving in England in 1902 en route to cover the Boer War for the Hearst newspapers (only to find out the war had ended), he stayed on in the nation’s capital to experience the impoverished citizens of London’s East End. Photographers are voyeurs at heart and London’s early work in the East End shows how the progressive movement (London’s political left) had moved on from the issue of slavery to England’s workhouses of the early 20th century.

London’s camera accompanied him and his wife, Charmian, to the South Pacific on his custom built ship, The Snark. The content of these photographs changed dramatically from street documentary (London’s East End) and war reportage (Russo-Japanese War) to a much lighter, vacation-snapshot style. These particular photographs are those of a tourist with an ethnographic gaze, where photographer and South Pacific islanders are strangers in a primitive headhunter, non-white world. On a trip to an island market, Charmian is photographed packing a small caliber side arm. London, hoping to use the photograph for publication, must later defend the snapshot of his wife to publishers who do not believe the photograph is of good taste for western consumption. London reprimands his publisher, explaining that his photographs and his writings have only one purpose: to reveal the truth. By the end of his written rant, he shouts to his publisher that, “he [London] is glad he is in the South Pacific; and his publisher in North America.”

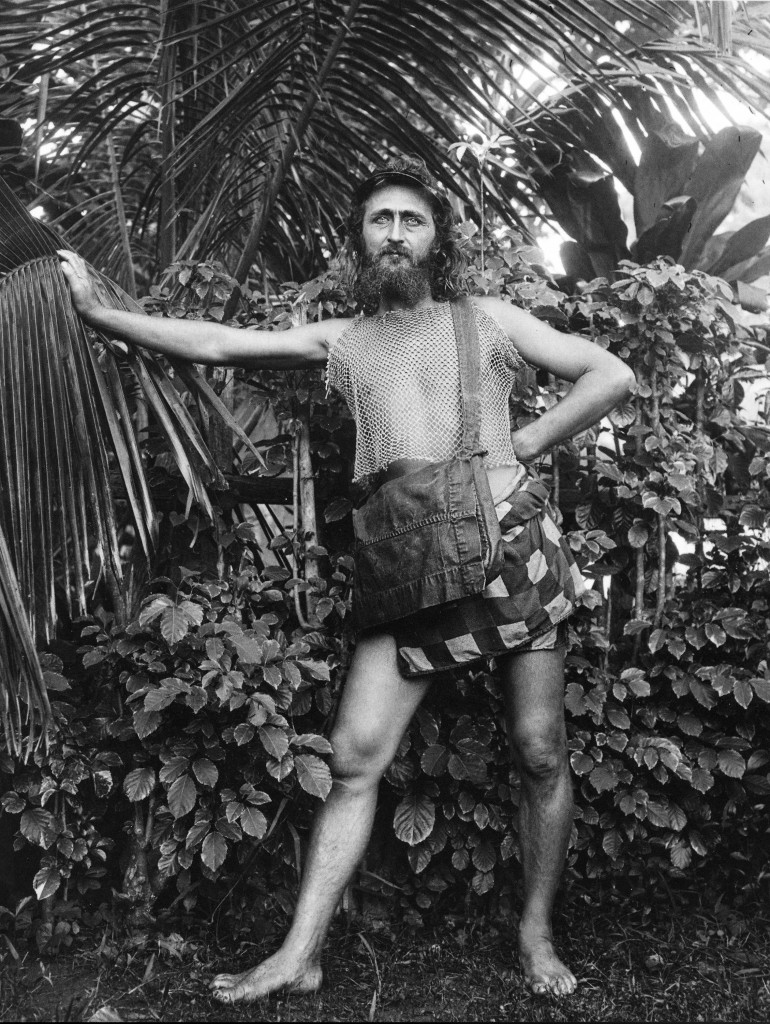

Ernest Darling, “Nature Man,” by Jack London

Another example of London’s desire to present an unvarnished account of the South Seas for western consumption is a beautiful, full-length portrait of “Nature Man” Ernest Darling. Darling as described by London “was an inspiring though defeated figure.” Darling’s portrait, if covered only to reveal his face, reminds me of a “hippie” type figure of the late sixties and early seventies. I am sure Darling would have been as comfortable walking around “Haight-Ashbury” in San Francisco as he was on the South Pacific island of Tahiti in 1907.

The exhibit of fifty of London’s photographs is presented by the Maritime Museum of San Diego, and is hung down in the lower hold of The Star of India. The digital prints made for the exhibit have more contrast and are a bit sharper than the prints reproduced in the book. London’s camera work is professionally hung and lit with ample text for viewers to understand how “f/8 and being there” is the essence of the craft of photography.

All Content ©Copyrighted 2012 Craig Carlson All Right Reserved